AUTHORS

Stephen Orr Q&A

Bio:

Stephen Elder Barr-Smith Bonython Orr

Born: 4 September 1969, Calvary Hospital, North Adelaide

Spouse: Henrietta Vance Orr (m. 1972)

Children: 14, including Charles ‘Lizard’ Orr, Samantha ‘Boulderstone’ Orr

Education: Gilles Plains Primary School, Gilles Plains High School, Gilles Plains University (GPU)

Influences: The guy who lived at 14 Ramsay Avenue and sun-baked nude in his back yard despite everyone watching over the fence

The internet states that Stephen Orr is an American gardening writer, but this seems unlikely. Another Stephen Orr lives in Adelaide and writes strange, overlong, self-indulgent novels. He survives (and thrives) on the kindness of strangers, independent bookshops like Matilda’s, and his family and friends. As of 5 May 2021, he claims to be writing the world’s first ungooglable novel which, when completed, will cease to exist. Proudly, he has never been invited to a writers’ week outside of his hometown, and libraries avoid him like the plague. There is some chance that Orr himself is a hoax.

1. Why do you tell stories?

I’m convinced that people are born with the story gene, or they’re not. And if you are, it’s what you’ll end up doing (despite how much you try to be ‘sensible’ and do other (ie paid!) things. It’s also the way you try and make sense of the world (for your own sake), but mostly, it’s because you get a deep enjoyment, a thrill from the vision, the words, the book, and the responses.

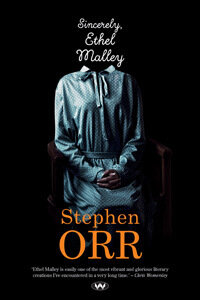

2. Describe Sincerely, Ethel Malley in one sentence.

This is a book about a woman who finds a unique, strange, troubled way of dealing with life, and her own history.

3. How did the concept of writing a novel from the perspective of a fictitious sister of a fictitious character come to you?

I read Michael Heyward’s The Ern Malley Affair, in which Heyward has a few passages describing Ethel bringing her dying brother cups of tea, vegetable soup. It occurred to me that the accumulation of these details could tell a whole new story. From the start, I found Ethel more interesting than Ern. She was the one (in a doubly fictitious way) who drove the story, sent the poems &c., and I thought what if she had an even bigger role in the affair? Then Ethel came alive and demanded I write what she wanted, her version of the truth. Eth was just so likable (in a very complex sort of way) that I had no choice in what I wrote. And the whole time, she was, has been, is looking over my shoulder. So for those people who say something is ‘just a story’ – no, no, no. Fictional characters are far more real than anyone who ever has or will walk the earth.

4. How did you feel about writing real characters, with immediate family members still alive, into the novel?

I was always aware of my responsibility to Max’s daughter, Samela, as well as the memory of others who took part in the story. But I also had to follow my instincts as a writer. I showed Peter Goers and Samela the manuscript early on, and both have been gracious in their support and understanding. Samela has come from a life of words and ideas and, like Max, knows the importance of allowing a thought, an idea, a myth like Ern, to grow. In the end, these stories are greater than the people who make them and curate them and write poems and novels about them. Maybe in a thousand years the myth will have grown to the extent that fact and fiction are no longer discernible, and there’ll be some sort of cult of Ern, with people reciting the poems at weddings and funerals and bowing down in front of a giant Ethel on Sunday mornings!

5. 1940s Adelaide is drawn very evocatively in the novel—do you now walk around our modern-day city with a sense of loss or an acceptance that time marches on?

Yes, everywhere. We seem in such a rush to eradicate the past in this country. Walking down North Terrace provides me (as it did Ethel and Max) with a few sandstone moments. Places become the people who lived and worked in them. We shouldn’t discount this (but in Australia, often do). I’m old enough to remember the sound of the horse walking along Burleigh Avenue, Pennington, and the milkie stopping to make deliveries. I think nostalgia is out of favour, but we mustn’t confuse this with the act of learning from the past. Just describing how someone dressed – good shoes, a tie – to go to the shop for groceries, explains how people viewed the world then.

6. Where do you feel the Ern Malley poems sit within the history of Australian literature? Pastiche or something significantly more substantial?

I think the Ern Malley poems have lasted, and read beautifully. I think time has a way of ‘softening’ texts, erasing the pencil lines, sanding down the edges, blurring real and not real, and what you’re left with (if we value it enough, and we don’t) is something you and your culture have accepted as valuable. The poems are valuable. The story around them is valuable. And in the end, it doesn’t matter how something is made, or by whom, when – all that matters is that it means something to us now.

7. In our post-fact age does it feel nostalgic to write something predicated on the notion of authenticity?

The most important parts of this book, perhaps, are the scenes in which Max gets up in court to defend the value of a few poems he knew were fake. The poems, in a sense, were irrelevant. It was his right to publish them. And now, today, we’re told we can’t say certain things because they’re not ‘correct’ or might offend someone. And if we give in to physical censorship, eventually we stop thinking those thoughts. Quite Orwellian. My view is that Max, I, anyone, should be entitled to say, publish, sing, paint anything we like. That much is at stake in this ridiculous cancel culture.

8. When and where do you write?

I used to teach English, but I think I’ve been ‘de-platformed’ by the next generation. The phone, as it is, has stopped ringing. So I have time to write at home, in my study, cursing the guy across the road with his angle-grinder, the mower guy. I have a study full of books, because maybe the words leave the pages, float around the room, in and out of my head. Sometimes I just write for hours, and enjoy the experience, still, as I did when I wrote some awful novel when I was sixteen. When I was about nineteen, I wrote a short story (long since destroyed) about a man called Michael, and he’s ninety, in a nursing home, dementia, and he has a shelf of books (he’s written, but few people have read) beside his bed, and the nurses come in and say, ‘You wrote those?’ But no one ever takes one from the shelf, and reads the blurb, let alone the book. This is the pact writers make with time. I think I had Michael dying happy. Why, is the great mystery of human creativity.

9. What are three things that sustain you as an author, or while you’re writing?

Coffee, Bach, and those few favourite pieces you read over and over (for example, James Agee’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915).

10. Name three books that you couldn’t live without.

Borges Collected Fictions

Patrick White The Vivisector

Malcolm Lowry Under the Volcano

bonus question:

What book are you shy to admit that you’ve never read?

Infinite Jest (I’ve been stuck on p. 124 for a few years)